UNWTO: With COVID-19, global tourism is the worst affected of all major sectors – an emergency for developing countries and small island developing states (SIDS)

Last Saturday, a relative in the USA told me that with a very heavy heart, she and her husband had just cancelled their Caribbean holiday for this winter. The hope is that it will be possible next year.

At the 75th Session of the UN General Assembly, the Caribbean government representatives who spoke all pointed to the devastating impact of COVID-19 on their economies. Prime Minister Dr Herbert Minnis of The Bahamas reminded the Assembly that tourism is the main earner for his country and with the drastic decline in visitor arrivals since the start of the pandemic, his country experienced an unprecedented rise in unemployment. Foreign Minister Jerome Walcott of Barbados stated bluntly that the “novel coronavirus has stripped us bare!†Foreign Minister Peter David of Grenada pointed to the negative growth which his country will be registering this year. These and other discussions and reports about the region’s dependence of tourism led me to this week’s topic.

TOURISM AS TRADE IN SERVICES

There are some people who still find it difficult to believe that tourism is an export, but it is. Tourism is classified as ‘trade in services’. As a reminder, tourism now contributes 20-50 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) of several countries in CARICOM.

Trade in services is about the sale and delivery of intangible products, or what used to be called invisible trade. International trade in services is now regulated by the World Trade Organization (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS).

Under the GATS, services are delivered in four modes:

- Cross-border.

- Consumption abroad.

- Commercial presence in the consuming country.

- Temporary movement of natural persons.

Tourism is mode 2, as visitors travel to the Caribbean to consume the services and products being offered in the countries.

There are a wide range of services which can be traded, and the Caribbean does trade some other services besides tourism, but not on a large scale. These other services include architectural, legal, health, educational, financial, cultural (creative industries), energy, transport, sports, and consultancy, among others. The region’s trade in these other services is not as developed as it could be.

To develop the services sectors and further explore trade in services require good data. The CARICOM region still has difficulty collecting disaggregated trade-in-services data. By ‘disaggregated’, this means information on the volume and value of trade with specific countries or a specific service. The data mainly comes from the balance of payments published by the central banks. Often information on trade with a specific country has to be secured from that country, especially developed countries. The trade is primarily undertaken under WTO rules and the commitments to liberalisation (market access) made in the WTO. The only free-trade agreement which contains trade in services is the EU/CARIFORUM Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA).

So, tourism is the most developed service trade in the region and it is a very open sector. It is also the sector for which data is quite readily available at the national level through the tourism authorities, at the regional level through the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO), and at the multilateral level through the UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), not to be confused with WTO.

CARIBBEAN TOURISM’S RECOVERY FROM COVID-19

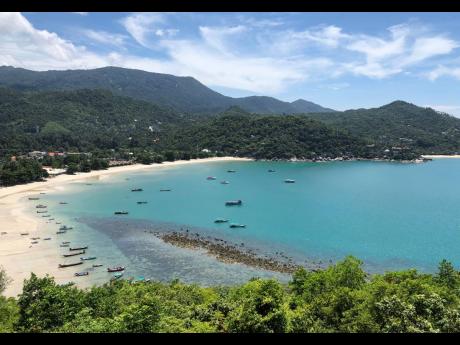

Tourism, which requires movement of people by land, sea and air, and their accommodation, has been severely impacted at the national and international levels as UNWTO stated. Much has been written and discussed about this impact, especially on SIDS and particularly the Caribbean, which has become very dependent on tourism through the years.

Caribbean countries have reopened borders and devised and implemented protocols in the hope that visitors will begin to return and the winter season can be rescued. The focus has been on the recovery of the sector. One factor, which seems to be overlooked, is that tourism is actually a luxury item. Although global travel has increased at phenomenal rates over the years, a foreign vacation is not at the top of the list of priorities for a household in an economic recession.

I and others have stated that we cannot ignore the international context. There are problems out there over which Caribbean governments have no control. The source markets are mainly the USA, Canada, United Kingdom and member states of the European Union. These countries are still battling to contain COVID-19. As cases continue to increase, some countries have had to reimpose additional restrictions. These economies are not improving satisfactorily and unemployment figures remain high. With their own domestic tourism suffering, governments and industry interests are more likely to encourage nationals to take ‘staycations’. The situation in the USA is particularly worrying. Twenty-nine states are still experiencing spikes and the president has now joined the list of those infected and hospitalised. This is all complicated by the pending elections and their likely outcome.

The medical fraternity is also concerned about the coming winter season, which is likely to bring further increases in COVID cases.

Add to this the crisis in the airline industry, where airlines are reducing staff and cost, some hoping that they can receive recovery support from governments. The cruise ship industry is also in a critical situation and it is not clear when cruises are realistically likely to resume.

The countries of CARICOM are hoping and planning for a recovery, and I do hope this will happen sooner rather than later. But, I also hope that contingency plans are in place.

This article which was originally published by the Jamaica Gleaner was submitted by Elizabeth Morgan, Specialist in International Trade Policy and International Politics.